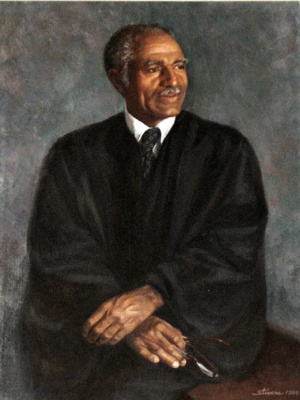

Judge William B. Bryant

HISTORY

In the fall of 1987, Roger Adelman and Professor Sherman Cohn of Georgetown went to see United States District Judge William B. Bryant to enlist his support in establishing an American Inn of Court and to obtain his consent to naming the Inn “The William B. Bryant Inn.”

Judge Bryant approved of the concept of the Inn and, although initially reluctant, was persuaded that it could be named for him. In November 1987, after the charter had been granted, a small group of lawyers and judges met to organize the 41st American Inn of Court, dedicated to trial practice skills and named after its most respected founding member, Judge William B. Bryant.

Lawyers who appeared before Judge Bryant, whether as prosecutors or defense counsel, respected him because he was clearly interested in doing justice in each case, justice both for the prosecution and for the defendant before him. His opinion as to what constituted justice was developed over the course of his long life, including his legal career as both prosecutor and defense counsel, and as a judge he was able to put his opinion into practice. And he continued dispensing justice until he died in 2005 at the age of 94.

The stark facts of Judge Bryant’s life, as set forth on the web site of the Historical Society of the DC Circuit, do not explain who he was or why so many of those who knew him loved and respected him.

Born 9/18/1911 in Wetumpka, AL

Died 11/13/2005 in Washington, DC

Federal Judicial Service:

Judge, U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia

Nominated by Lyndon B. Johnson on July 12, 1965

Confirmed by the Senate on August 11, 1965, and received commission on August 11, 1965

Served as chief judge, 1977 – 1981

Assumed senior status on 1/31/1982

Service terminated on 11/13/2005, due to death

Education:

Howard University, A.B., 1932

Howard University School of Law, LL.B., 1936

Professional Career:

U.S. Army, 1943-1947

Private practice, Washington, DC, 1948-1951

Assistant U.S. attorney, District of Columbia, 1951-1954

Private practice, Washington, DC, 1954-1965

Judge Bryant later described Wetumpka, Alabama, as “just a wide place in the road.” Within a year of his birth, the Bryant family moved to Washington D.C., in part because his grandfather, a store owner, had been threatened by a mob. Judge Bryant graduated from Dunbar High School, the highly regarded school for “colored” children, and in 1932 from Howard University College of Liberal Arts. During the next several years he worked as an elevator operator, duplicated records for the Recorder of Deeds, worked as a mail messenger, and other similar positions, while enrolled at the Howard Law School. After graduating first in his class in 1939 and being admitted to the District of Columbia Bar, he was unable to find a position as a lawyer in the segregated community of Washington, D.C. Ralph Bunche, head of the political science department at Howard, engaged him to collate and coordinate research for a project by Swedish Sociologist Gunnar Myrdal on the effects of racial segregation, which became Myrdal’s seminal work, An American Dilemma.

During World War II, Judge Bryant worked for the Bureau of Intelligence at the Office of War Information. Joining the army in 1943, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel before his discharge in 1947. On return to private life, Bryant opened a private law office on Fifth Street, representing individuals in both civil and criminal cases. In those days, before the Criminal Justice Act, a lawyer would sit on the side in the arraignment court of the Court of General Sessions (now Superior Court) and hope to be assigned to represent a defendant who would be able to pay a small fee. Judge Bryant quickly gained a reputation as a skilled trial lawyer. Prosecutors, who were losing cases to him, suggested he apply to the United States Attorney’s office. Although no African American assistant had ever appeared in the District Court (where all felonies were tried at that time), Bryant asked the United States Attorney at his interview whether he would be promoted to the “big court”, if he “cut the mustard” at General Sessions. The US Attorney at the time agreed, and the rest is history.

After several years as a prosecutor, Bryant returned to private defense, joining the firm that became Houston Bryant and Gardner. Probably his most important case during this time was that of Andrew Mallory, who was charged with raping a woman in an apartment building laundry room. There was no tangible evidence against Mallory, but after 7 ½ hours of interrogation he confessed. The trial court and court of appeals rejected Bryant’s argument that the confession should be suppressed because it had been extracted in violation of Rule 5 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which required that officers take an arrestee to a magistrate “without unnecessary delay.” Bryant took the case to the Supreme Court and, because of his familiarity with the location of the courthouse, police station, and committing magistrate, was able to tell one of the justices during the argument that the magistrate was available six days a week and a few steps from police headquarters. The resulting unanimous decision, in an opinion by Justice Frankfurter, held that confessions obtained during an unnecessary delay between arrest and arraignment are inadmissible. Mallory v. United States, 354 US. 449 (1957).

In a murder case that had some notoriety in the 1960’s, Bryant represented James Killough through three trials and two appeals, one en banc. Killough’s first confession in violation of Mallory was suppressed but he was convicted of manslaughter on the basis of a second confession made a day later to a police officer. The Court of Appeals en banc held that this confession should have been suppressed as fruit of the poisonous tree. Killough v. United States, 313 F.2d 241 (D.C. Cir. 1962). At the retrial, the government offered a confession to a jail intern. This too, on appeal, was held inadmissible because it had been taken under circumstances that implied confidentiality. Killough v. United States, 336 F.2d 929 (D.C. Cir. 1964). A third trial began on October 8, 1964; Killough was not convicted and was released the following day.

In 1965, President Lyndon B Johnson appointed Bryant to the United States District Court, the second African American to serve in this court (the first was Spottswood Robinson). In 1977 he became the first African American to serve as Chief Judge of the court. Although he took senior status in 1982, he continued to hear cases until shortly before his death on November 14, 2005. Bryant was strongly opposed to the sentencing guidelines, which he believed might prevent a judge from imposing what he considered a just sentence in a particular case. While a senior judge he would hear criminal cases that other judges were unable to reach but with the caveat that the case would be returned to the original judge for sentencing if there were a conviction.

Judge Bryant handled many significant civil cases during his 30 years on the bench, although his heart was probably with the criminal justice cases. One civil case involved the 1969 election of president of the United Mine Workers. The election, which had been won by W.A. “Tony” Boyle, was challenged by supporters of Joseph A. Yablonski, his opponent; Yablonski and his wife and daughter had been murdered three weeks after the election. After a trial, Judge Bryant nullified the election and ordered a new election, to be supervised by the Department of Labor. The second election was won by a Yablonski supporter. In 1974, based on statements by two of the three convicted murderers, Boyle was convicted of murder in connection with the death of the Yablonskis.

One may speculate that the case closest to Judge Bryant’s heart was the suit brought in 1972 by the Public Defender Service challenging conditions at the D.C. Jail. The case was assigned to Judge Bryant. Pat Hickey, director of PDS when the case was filed and attorney for the plaintiffs during the 31 years the case was pending, has recounted that early in the case Judge Bryant called counsel into chambers and said he wanted to visit the jail to observe conditions immediately, so he could view the conditions as they really were, without any cosmetic changes. Judge Bryant presided over this case until it was finally resolved in 2003, after overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and inadequate medical and mental health care had been finally been improved to the extent that the jail received national accreditation. See, e.g., Campbell v. MacGruder, 416 F. Supp. 106 (D.D.C. 1975), consolidated with Inmates of D.C. Jail v. Jackson, 416 F. Supp. 119 (D.D.C. 1976).

Judge Bryant wanted every person who appeared before him to have the feeling that justice had been done. He cared about his clients, his colleagues, his law clerks, his assistants, the witnesses and defendants who appeared before him, and of course for his family. It is an indication of the respect that the Washington D.C. community had for Judge Bryant that the Chief Judge of the District Court on behalf of all judges of the court sought and obtained the support of Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, Senator Patrick Leahy, and Senator John Warner, for their proposal to name the Annex to the Prettyman Courthouse for him, an honor rarely given to living persons. The bill naming the annex for Judge Bryant was signed by the president two days before the judge’s death.

At Judge Bryant’s funeral in November 2005, and the Inn’s memorial banquet in May 2006, many of those who knew him sought to explain why he was so universally loved and admired. In September 2011, the 100th anniversary of his birth, the District Court and the Inn held a celebration at which lawyers and others who had know him spoke. The record of those proceedings is available at 287 F. Supp. 2d. In addition, William B. Schultz, one of the judge’s law clerks, interviewed Judge Bryant at length for an oral history that is available on the web site of the Historical Society of the D.C. Circuit.